White glove CFO services for sophisticated financial clientele

Who We Serve

A versatile approach with consistent results.

Real Estate Private

Equity Funds

Accredited

Investors

Real Estate

Developers

Real Estate

Family Offices

From the Stonehan Vault

High-touch services with institutional expertise

Real Estate

CFO Services

Accredited

Investors

Real Estate

Developers

Hard Asset Management

Private Equity

Administration Services

Business Consulting

Private Banking &

Lending Relationships

Consolidate Net

Worth Picture

Spend Management

Featured Podcast Appearance

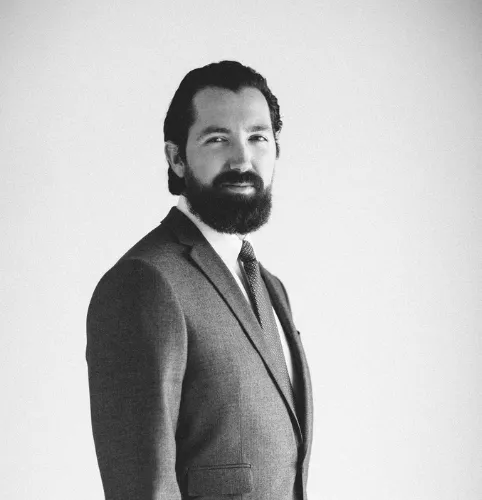

James Bohan on the RIZZ Podcast:

How financial strategy can supercharge marketing and business development in commercial real estate.

In his appearance on the RIZZ Podcast, James Bohan, founder of Stonehan, reveals powerful insights on using financial strategies to elevate your real estate marketing and growth. Discover James' unique journey from family dinners discussing property deals to innovative solutions for affordable housing and boutique hospitality investments.

Watch this if you're serious about keeping more of what you earn, and building a portfolio that lasts

Our Proven Track Record

Client saved over $200,000 in taxes

Client Challenge:

Starting and growing a business is no small feat, and navigating the complexities from formation to exit can be daunting. One of our clients faced this challenge, needing expert guidance to structure their business in a way that would optimize their financial outcomes, especially when it came time to sell.

Stonehan Accountancy Solution:

From the initial formation of the business, we worked closely with the client to design a structure that would not only support their growth but also provide significant tax advantages when it came time to exit.

Outcome:

By meticulously planning and strategically structuring the business, we were able to save our client over $200,000 in taxes upon the sale of their business. This wasn't just about compliance—it was about foresight, strategy, and maximizing financial gain.

Key Takeaway:

Stonehan Accountancy is dedicated to more than just managing numbers. We offer strategic insights and proactive planning that lead to substantial financial benefits. From the very beginning to the final sale, our expertise ensures that every decision made is one that contributes to your financial success.

Are you ready to see how strategic business structuring can transform your financial outcomes? Contact Stonehan Accountancy today to learn how we can guide your business from formation to a successful exit, with significant tax savings along the way.

Seven Critical Factors Most CPA's Overlook

There’s a difference between working with a CPA and working with an entrepreneurial CFO focused on serving fellow entrepreneurs. At Stonehan we guide our clients by going beyond surface level investigation, into the nuances that only sophisticated investors can appreciate.

Real Estate Private Equity Services

Comprehensive Fund Administration Services

Outsourced CFO Support

Strategic Tax Advisory

Consolidated Financial Reporting

White Glove Tax and Accounting

Ongoing Compliance

Back Office Support

Start Up Consulting

Advise on fund and management company organizational best practices

Business model consulting

Review and advise on fund formational documents

Attorney and compliance partner network referrals

Investment Accountancy

Fund Accounting

IRR & Performance Calculations

Asset Management Reports

DDQ Compliance Assistance

Investor Portal Management

KYC/AML/Accredited Investor Due Diligence Management

Fund Formation Consulting

Audit Coordination

Why Stonehan

As a CFO with both institutional and entrepreneurial experience, Stonehan has the unique ability to offer strategic, personalized, and forward-thinking financial solutions that resonate with real estate family offices and high-net-worth individuals.

4th generation real estate developer

Institutional quality reporting, boutique quality attention

⚡ Site Built with BAMF Technology ⚡